To be honest, before this fall I had never taken part of a Design Sprint. It always seemed like a toy for the big boys in startups to play with. Then Eaze happened...

To walk a thorny road, we may cover its every inch with leather or we can make sandals.

I'm still wrapping up my masters degree. The course University of Minho provides has a peculiar characteristic. It doesn't matter what specialty you are attending, every student in the final year of their course has to take part in a rather unique class. You pair up with 7 or 8 of your peers and a professor tells you: Are you all in the same group? Great. Now, have an idea and ship a product. You have 4 and a half months. We want an MVP and two full reports composed of technical documentation, user experience, system requirements analysis, product vision and a business model and financial analysis and why are you still staring at me? Chop-chop!

I won't lie, the pressure was building up on us. I decided to have a word with Roberto about it. Well, he's the CEO... I thought. He MUST have some idea of where software comes from.

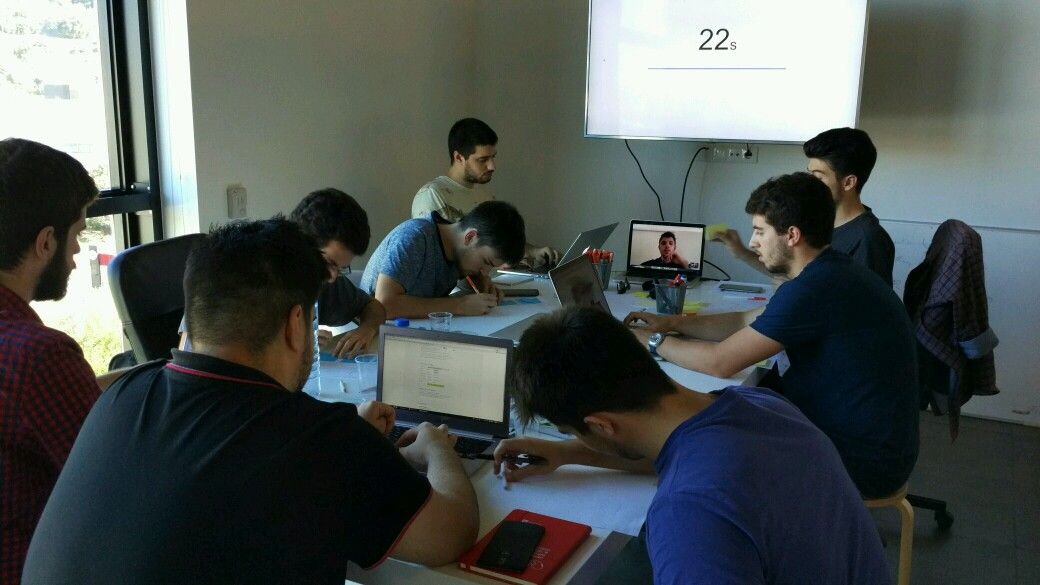

After finding common ground on what could be built I asked him what direction we should take. The project was ambitious and had a lot of different possibilities ahead. He told me something along the lines of I don't know and neither do you. You can't know the answers if you don't ask the right questions first. He convinced me to do a design sprint and even volunteered our office space. Since neither I or my group mates had any experience with the process, Roberto was able to drag-uh... convince Francisco to help us.

A lot has already been said about how design sprints are great and awesome and how you should do one at least 3 times a day. We even got our Summer Campers to do one, here at Subvisual. But how do you take on the challenge of (a) doing a design sprint with 9 (!!) participants, one of them remote, and (b) doing it in the context of a project based on foundations imposed by the academia?

Condensing

Let's start with (a). We were on a tight budget regarding our time. As far as tight schedules go, ours was tighter than the Bee Gee's pants during the Staying Alive sessions.

It also turns out that coordinating Design Sprint exercises with lots of people is f*cking hard, especially if one of them is half-a-country away in an office roaring with people. I sat down with Francisco. There was no time to waste and everything non-essential had to be dropped. We took a long hard look to the Design Sprint Trello template and questioned the purpose of each exercise. We finally grabbed our metaphorical axe and started chopping away.

The Beauty and The Academia

Chances are sometime during your university years, you actually met some professors. They are a very special breed of humans whose main hobbies include wearing a tweed and taking way too much time to grade exams.

Ours made us realize this wasn't like other academic projects where complexity is king. It wasn't going to be a meritocracy and it didn't matter how much better your codebase was or how complex your system ended up being. Your idea, your approach, the hype you build around it, the development process, the market feasibility, those were the key areas that would make or break your idea. And to topple it, the process and approach you chose were focal. Besides the grade taking them into consideration, the pace at which the projects were expected to go demanded it to be agile and fast. If yours wasn't good enough, you would probably end up with a very complex system that wouldn't do what it was supposed to.

A non-working project was as good as dead so the first goal was to have something working.

As every good professor who stays up late at night wondering what's the best way to have students write reports, they had us writing reports. For. Everything.

And there we were. In an environment most university students aren't accustomed to, trying to develop a wannabe-company from scratch in 4 months, with all the burden that academic projects bring into the table but without the actual inherent (theoretical) meritocracy.

As it turns out, these restrictions go really well with design sprints. In both cases, you want to have something out fast and validate the idea. As early as a couple of weeks into the project we already had a prototype out. You also want to set the converged result in stone. Well, that fits with the document, document, document philosophy professors so much enjoy. Everything we spoke about during the design sprint was documented. Our Drive was filled with brainstorm results, spreadsheets and forms. Hell, even the goddamned post-its were documentation. We took pictures and threw them into the official document. The result was a wet dream for document-obsessed grading systems.

The documentation part was easy. Boring, yes. But easy. The main issues with this startup-like mindset mixed with the academic context arise when you get to the problem statement. University students, influenced by their professors, tend to define a "good system" as something capable of mind-bending complexity. We try to make everything look cool and by the book. If it was physically possible to have a web app brew its own beer and pour it into a glass, we would try to implement it. The better looking, the more feature rich the system is, the better developer you are, the higher the grade. The environment you live in during your academic years fosters this idea. In real world, this isn't as true. As I said before, it had to work. We wanted an MVP, not a bloody Google-ish ecosystem.

.

.

There isn't much I can tell you regarding this tendency. It's probably deeply ingrained in you by now. It gets worse if you are indeed a perfectionist. And boy, did we have perfectionists in that group of people. Myself included. You'll just have to question every feature proposed during the sprint.

Is this really necessary? Would adding it increase the value of our product? Would removing it

decrease it? Will I be able to do it in due time without going insane?

During the sprint, try your best to ignore the technical complexity. Don't even think about it.

Rule of thumb: if at any point your idea seems cool or fun to implement, you're probably doing it wrong.

Focus on the product and the path it is taking, instead. Technical details and doing cool sh*t to impress your professors comes later. Even if those mean a higher grade. Technical complexity isn't going to save you if you can't implement it in good time. Preferably without losing your sanity. In fact, complexity can help you get stuck and demotivated. Just ask that one guy in our group that ended up implementing geolocation and map features during 3 whole months.

Adding in features, making a kickass AI, reverse geolocation and even having your app do its own beer brewing, none of that matters. Not during the design sprint. What you want is to get rolling. Select a path for your product, validate the idea and the market, build a prototype, refine, iterate. The product may change its path. You don't know. You can't know. But if you build up solid foundations, you are much more comfortable to make the change when the time for that decision comes around. You'll have data, insights and can make a justifiable and rational decision instead of following your gut.

The Results

So, what did we get out of this? What were the tangible results that helped us succeed?

Well, the most obvious one was the idea and goals. We all knew what we wanted to do. We all knew what we were going to do. We didn't need to oversell the product or the idea and all decisions were rationally justified.

There was no excess of features or complexity. We were ready to start it right off. This is especially important when you have a team with such large numbers. It's incredibly easy to have someone in your group of pseudo-founders that does not comprehend the vision, that does not share it. But after those long hours inside the Subvisual office, we all had a common goal and felt confident following it.

Half of us had never worked together but when everyone knows what everyone else is going about, most barriers that come with putting together a new team just fall apart. Oh and those petty discussions that sometimes pop up in every group project, especially during the later execution stages, were gone. Everytime we had to question something or were unsure, we just tracked back to what we had agreed upon in the design sprint that was that.

Developing the prototypes and performing usability testing was definitely one of the most useful steps and we don't see nearly enough in the academic world. We had constant feedback, we knew what worked and what didn't because we were able to get data and insights on it.

When you develop a prototype you are materializing your idea, your vision. As I said, in large groups it's easy to have someone get sidetracked from the vision. But when you convert abstract concepts into something tangible, when you force everyone to actually display what they invision for the product, you leave no room for error. There will be no subjectiveness because every single member of the team has to demonstrate what they see, explaining why, be subject to criticism and then select what's best for the product. You'll converge on a shared vision. And a shared vision makes all discussions fast, civilized and productive.

Almost every single time we had to debate something, we were actively solving a problem. Not raising a new one because of lack of communication or comprehension.

And after this vision was shared, materialized and fundamented through the prototypes and testing, were able to jump right into what actually needed to be done. I'm not exaggerating when I say that after those 3 days we were a full month ahead from the rest of the groups. Nearly one month before the first delivery came around we already had the documentation set up, two prototypes nearly finished and a REST API under development. Meanwhile, other groups were still debating whether their idea was good or bad and how to pull it off. I cannot stress enough how this was important.

It's essential to keep in mind that in the academia you're running against time and all of your efforts have to be documented. You're not networking, playing around with influences, attending meetups, looking for funding or having Starbucks while debating solutions with your fellow engineer friends. You're (unfortunately) working with the sole purpose of producing code and documentation. And fast. You can either define a plan, fundament it and be done with insignificant discussions, or end up arguing over the feasibility of an idea that no one knows whether it works or not because you haven't even brought significant data to the table. And you'll end up pulling all-nighters to finish a product that has no clear path, that has become the result of stitching the interpretation of 9 different people with different opinions resulting of their different experiences. All before midnight strikes because "holy f*ck, it's delivery day already? When did time fly so quickly?"

And when all is done, you'll have something you made. Something you can show and be proud of, instead of just spaghetti code that barely holds it together a few hours from delivery time.

The Aftermath

After developing the product, the question that followed was "what's next?".

We put a lot of effort and invested many man-hours into it. The project was actually built on solid ground, with sane decisions, following generally accepted principles. Since its presentation, we have been approached numerous times to continue the development. Even though it was an academic project, it has grown past that.

Eaze has been shown to the world and whether or not it will eventually see the light of day is something the future will tell. But the road is wide open and all the foundations were born inside that glass-filled room in those 3 late summer days. We made sandals, instead of paving the road.